In 2010, I spent two weeks in Rwanda. I stayed with Dutch diplomat Jolke Oppewal and his wife, medical anthropologist Henny Slegh. Their house and garden in Kigali were a welcome oasis in the turmoil, silence and sadness that still lay over the country in the aftermath of the 1994 genocide.

I visited a church turned into a memorial, where clothes, lying scattered across the pews, bore witness to the horrors their bearers had endured. That the country also offered glimmers of hope, I experienced in a village where Henny took me and where I, thanks to the operation of a Gacaca court (a tribunal at village level), saw victims and perpetrators interact; very touching.

From Kigali, it is a few hours-drive to Goma in DR Congo. I wanted to go there to see a bit of the art and antiquities trade, and Jolke knew where to find it. Some sort of corridor leading from the border to the city was safe, most of the town too, but the further surroundings were a no-go area, allowing us to only stay there one night.

An obscure trade

Omitting here a description of broken houses, stranded tanks, broken road surfaces and other traces of war, I take you straight to a roundabout in Goma-town where itinerant traders were offering (literally) thousands of wooden masks, statues, drums, chairs and other pieces. I had landed in the middle of the illegal trade.

One dealer explained that most of them had come from villages, where the population had fled. Some were decades old, they claimed, while others were of more recent origin. Most traders had dozens of rather similar, criss-crossed pieces.

Villagers had been unable to carry them along on their flight or they had given them up for a trifle to hawkers, who happened to be around at the time the villagers had been forced to leave their homes. Armed groups from Rwanda, who secretly operated in DR Congo in order to get a piece of the cake of minerals, had nicked the somewhat better ones. On their way home, they sold them just before the border, where I was at that moment, or just across.

A pained look

This must have been how things went more often in conflict-ridden areas, not only during the colonial period in the global south but also under the Nazi-regime in Europe: people are forced to leave their valuables behind or, at best, to sell them far below the price. Occupying forces pick up the best pieces or what they find in abandoned houses.

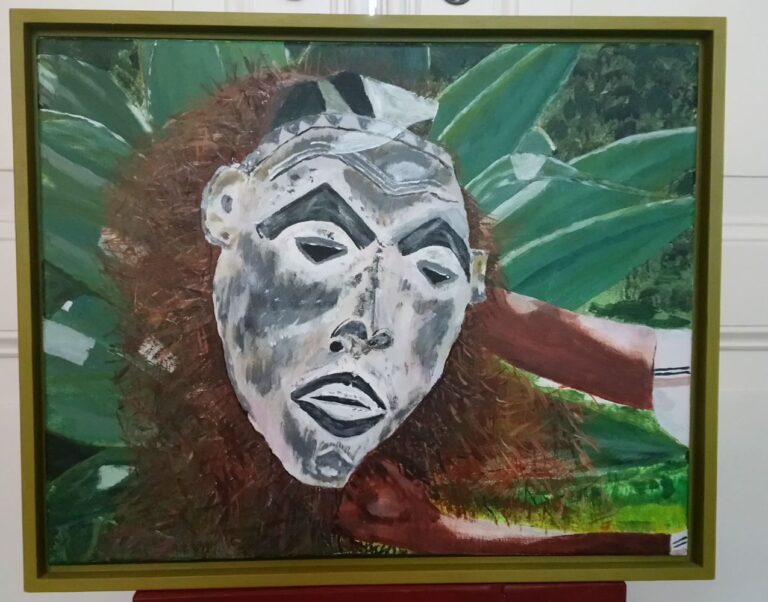

Observing our interest, the dealer suddenly came up with the mask. Immediately I was struck by the grief-stricken, sorrowful look and the loving hands of the dealer who held it. And my imagination put all sorts of questions in the mask’s mouth. Why am I here? In which village did you belong? Who brought me here? Why am I meeting you, a white man, here? What have you done to me?

Because of all unanswered questions, I did not even consider to buy it. It ought to go back to the place where it was created. Without asking the statue or the dealer for permission, I quickly took a few photos and of one of these I made this painting. The image inspired me to title my dissertation ‘Treasures in Trusted Hands’ and is now the logo of ‘RM* [restitution matters]’.

I dedicate this blog to this anonymous mask, its maker and the people who once may have used it.