An unprecedented large-scale restitution

Such a large-scale return of natural history objects is unprecedented, especially for the Dutch national collection and for natural history museum Naturalis, where the discussion on the colonial roots of natural history collections is still progressing rather reluctantly.

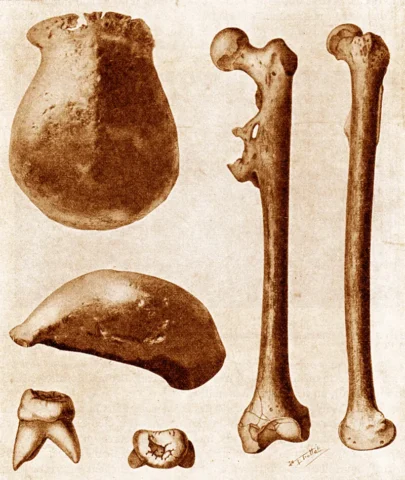

The skullcap, a molar, and a thighbone

The skullcap, a molar, and a thighbone

This is in contrast to a country like Germany, where the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin, which hosts a humanities centre, is deeply engaged with such questions. There, the humanities and the natural sciences are not regarded as two separate fields with nothing in common, but as two domains that are inextricably linked. Just as the Commission ultimately approached the fossil collection.

Objects and archives

The Colonial Collections Committee defined the fossils in its advice as ‘cultural objects’, not mere as objects of nature.

- ‘In order to be able to discuss the application for restitution the Committee was next faced with the question of whether the specimens in the Dubois collection are cultural goods in the sense of the Dutch Heritage Act. In this context the Committee refers to the explanatory memorandum to the Dutch Heritage Act, which states that finds such as these can be cultural goods: ‘Geological and biological specimens can also fall under the definition.’ [p. 16].

This makes them comparable with, for instance, objects from the British raid on the kingdom of Benin to Nigeria (2024) or objects from the war on Lombok to Indonesia (2023).

Furthermore, and to my knowledge for the first time, the Committee linked the restitution of museum objects inseparably to their ‘metadata’: letters, research notes, dossiers, and so on. This breaks with the prevailing practice of treating the restitution of objects and the restitution of archives as two separate categories. Indonesia has always emphasised that the return and ‘sharing of knowledge’ is as important as that of objects.

For the first time, this is now taking shape through a material transfer of data, so that the restitution concerns not only the object itself ‘but also its associated context and information’.

A step forward towards more collaboration

Another major step forward is the collaboration between Indonesian and Dutch researchers. This is increasingly being recognized, including at Dutch government level, as evidenced by a recent report of the Cultural Heritage Agency.

However, in practice, progress has remained quite limited until now (and I acknowledge my own share of responsibility in this as a white researcher). In this case, however, both Indonesian and Dutch scholars collaborated on this provenance research. This not only provides research with urgently needed new perspectives, but also makes clear that the study of this heritage is not an exclusive privilege of scholars from the Global North.

A new perspective on sources

The recommendation of the Colonial Collections Committee chooses to interpret the silences in the colonial archival material à la Ann Stoler as meaningful. It recognizes that such silences may point to tensions, to matters that were difficult to articulate, or to things considered so self-evident at the time that they did not need to be mentioned. Crucially is that these are now interpreted in favour of the Indonesian population.

Current line-up of Java Man in Naturalis

Current line-up of Java Man in Naturalis

I see this as an important step: in the past, I felt that much greater emphasis was placed on what was explicitly written down and on written evidence alone, while most of these sources could be found in the Global North and bring with them their own inherent limitations and biases.

The advice to restitute

Finally, the advice and ministerial decision rest on two main arguments:

- The first is a legal one: the collection was the property of the Dutch colonial administration and never became the property of the Dutch state; it is – in accordance with usage in international law – the property of the successor state: Indonesia.

- The second argument is the acknowledgment that the objects were taken against the will of the population, thereby inflicting injustice upon them.

Notably, the committee does not invoke here the arguments from the 2021 Dutch national policy vision that the objects are of ‘special significance’ to Indonesia and of particular historical importance. These were arguments that in this case would have been obvious. A broader weighing of interests is therefore still, just like in the other restitution cases, absent.

The aftermath of the decision

The decision to return a large part of the Dubois collection to Indonesia has been experienced in Indonesia as ‘emotional’. Naturalis is ‘grateful’ that they have been able to display the fossils in the museum for so long. The institute, however, struggled for a long time to acknowledge the legitimacy of Indonesia’s restitution claim.

In its reasoning, Naturalis was guided by:

- Decades-long beliefs about the separation between cultural and natural heritage. It argued that a fossil is incomparable with a colonial object that was looted.

- Neo-colonial prejudices about where science could be best conducted also surfaced: In their opinion, Naturalis was the ‘scientific hub’ with better research infrastructure and more comparison material.

- According to the institute, the object’s scientific interest took precedence over the claim of the country of origin.

Anti-restitution voice

Depot Naturalis

Depot Naturalis

Ultimately, Naturalis seems to have come to terms with it. That the Dutch government’s decision is hard to swallow for other natural history institutions, shows former director Jelle Reumer of the Natural History Museum in Rotterdam. In a Dutch daily, he called the restitution ‘a dangerous precedent’. ‘When you open this box of Pandora, you can ask questions about all the butterflies, beetles, rocks and plants ever collected in colonial territories.’ Until now, the return of colonial objects was usually about stolen art objects. ‘If those countries want everything back, the Netherlands will empty, and that also applies to the natural history museums of London and Paris.’

This response underscores the urgency of intensifying the discussion about the future of natural history collections with colonial roots, with close collaboration between the humanities and the natural sciences. The era in which these disciplines operated separately, and natural history museums could remain detached from societal developments, is definitively over.

- The author thanks Sadiah Boonstra, Hasti Tarekat, Wouter Veraart, and Robert-Jan Wille for their input.

- Pictures: Courtesy Naturalis Biodiversity Centre