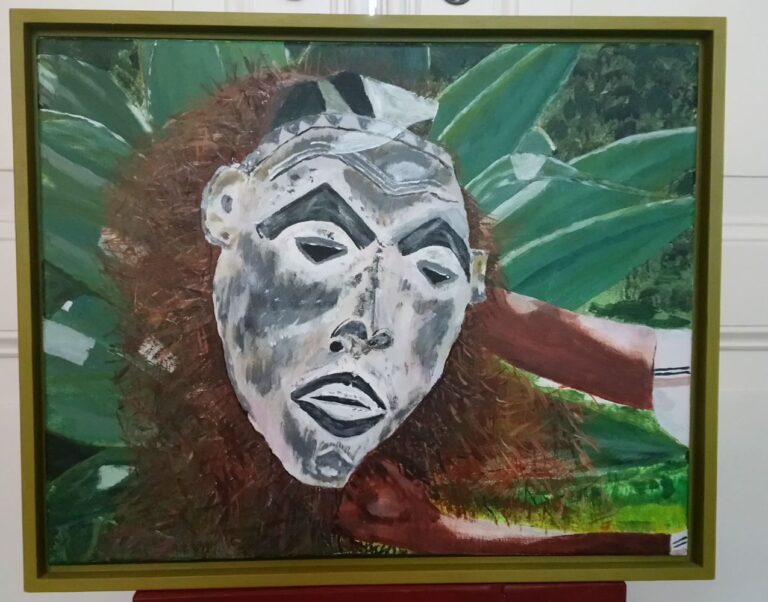

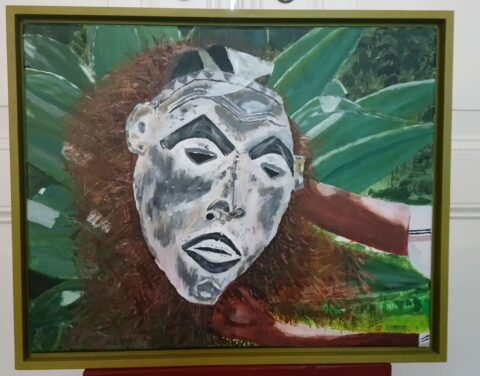

Dedicated to a mask, its maker and first users

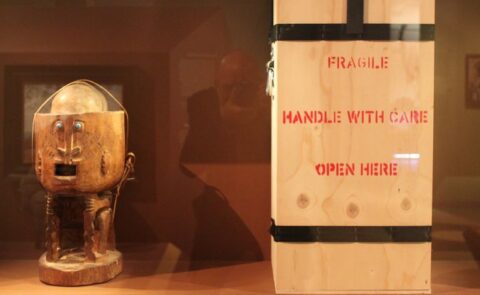

Long ago, I held this Congolese mask in my hands. The dealer claimed it to be very old; he was keen to sell it. But unlike other wooden pieces, which he offered for little money, he asked a big sum for this one. Perhaps, it was indeed old and valuable. Back then, the mask struck a chord with me. Nowadays, it still does.